The associated model and definition that demonstrate a partial recreation of this project can be downloaded here.

Edaphic Effects

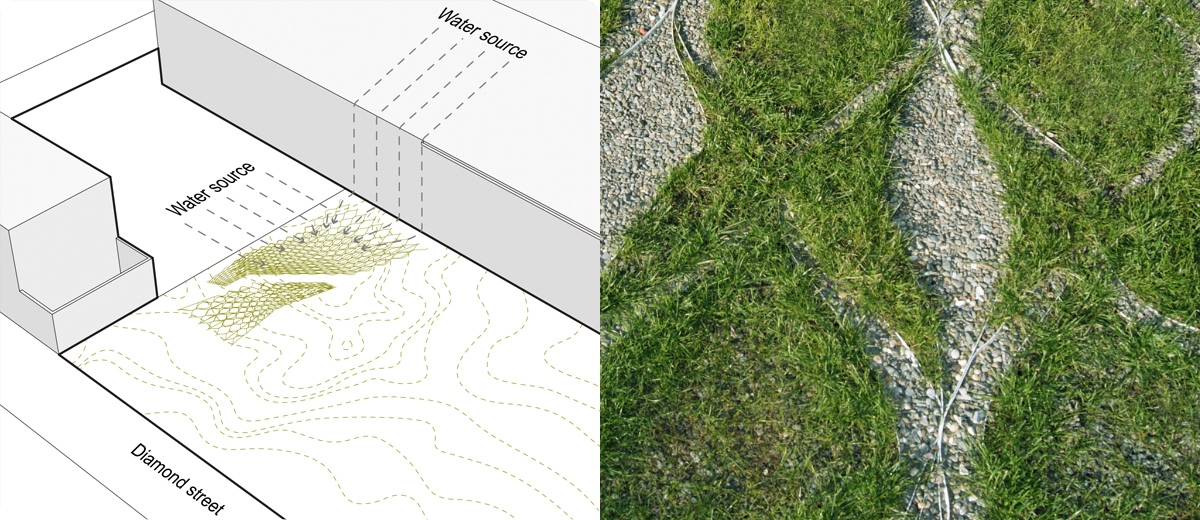

Parametric patterns produce infiltration infrastructure in-grade.

The parametrically-controlled geo-textile system following initial regrowth.

PEG Office of Landscape + Architecture, via www.suckerpunchdaily.com/2011/12/26/edaphic-effects/The Edaphic Effects project demonstrates PEG’s fascination with patterns as a design driver and the value of parametric methods in translating those patterns into form and material. “If ecology and systems are common frameworks used to describe the constellations of relationships that we see in the world” write Karen McCloskey and Keith VanDerSys, “then patterns are the ‘how’, or the means by which we come to know, understand or express these relationships.”1 They “exist outside such categorical distinctions as nature versus culture”2 while offering a framework that can tie ecological and infrastructural requirements without sacrificing aesthetic qualities.3

The project itself intended to demonstrate the potential of “incremental infrastructures” to improve the stormwater infrastructure of Philadelphia. To do so, a dispersed network of geo-textiles was proposed as a means of increasing water retention across vacant lots. Unlike the straightforward layering of traditional geo-textiles, the proposed design employs a more complex pattern that sees the geometry and infill of each geo-cell carefully controlled on an individual basis.4 This, in turn, allows the material profile to be tailored to the needs of each site while also producing a uniquely expressive surface.

To achieve this, PEG began by defining two consecutive forms of patterning.

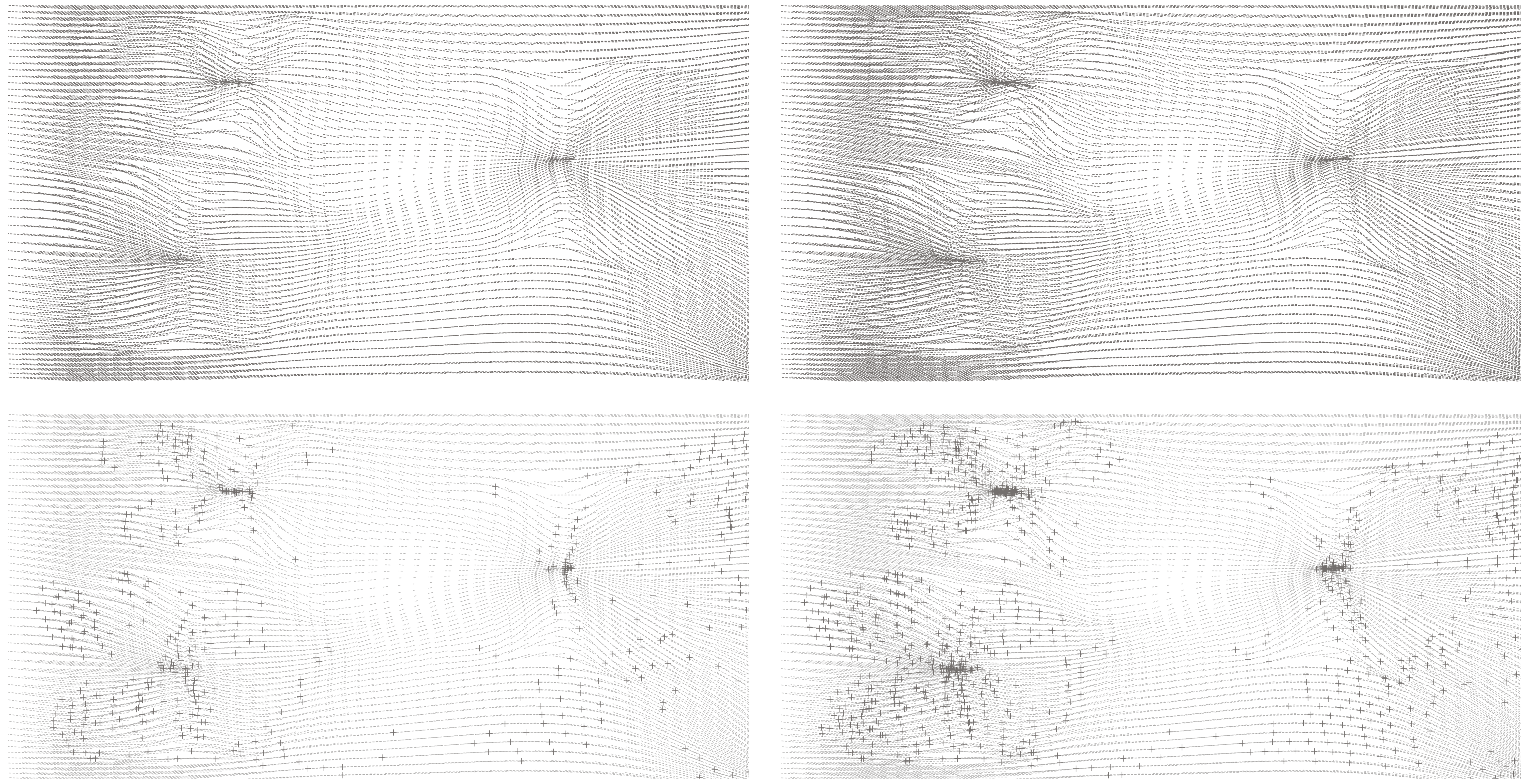

First, they developed a series of “surface patterns that are mapping forces”5 that responded to a topographic model of the site and indicated areas on site where water would likely collect after rain.

Subsequently, a second pattern was introduced to translate this analysis into geometries that could be used to shape and organise the geo-cells. This meant that — unlike a standard geotextile — each cell was parametrically-defined in a way that allowed them to gradually change shape and size in response to the flow of surface water across the site. The geo-cell structure is thus able to respond to areas where more or less water is expected to collect, potentially increasing water retention while also expressing these hydrological dynamics through a complex arrangement of materials.

A script calculates the rough paths of surface water flows across the site

PEG Office, from Dynamic Patterns p. 70.In this project PEG give a clear example of how parametric methods can prove a powerful aid in translating valuable – but often difficult to decipher – quantitative data sets into responsive patterning systems. These can then be applied directly to site in a way that allows them to both reveal and affect the landscape conditions that their pattern initially derived from. Here this was achieved through two consecutive parametric patterning exercises, where “one is a flow pattern based on structuring relationships” and “the other is a module based unit that could be used for construction”6. Taken together, these work to define an inter-related rule set where quantitative and qualitative information sets are tightly correlated.

Reference Model

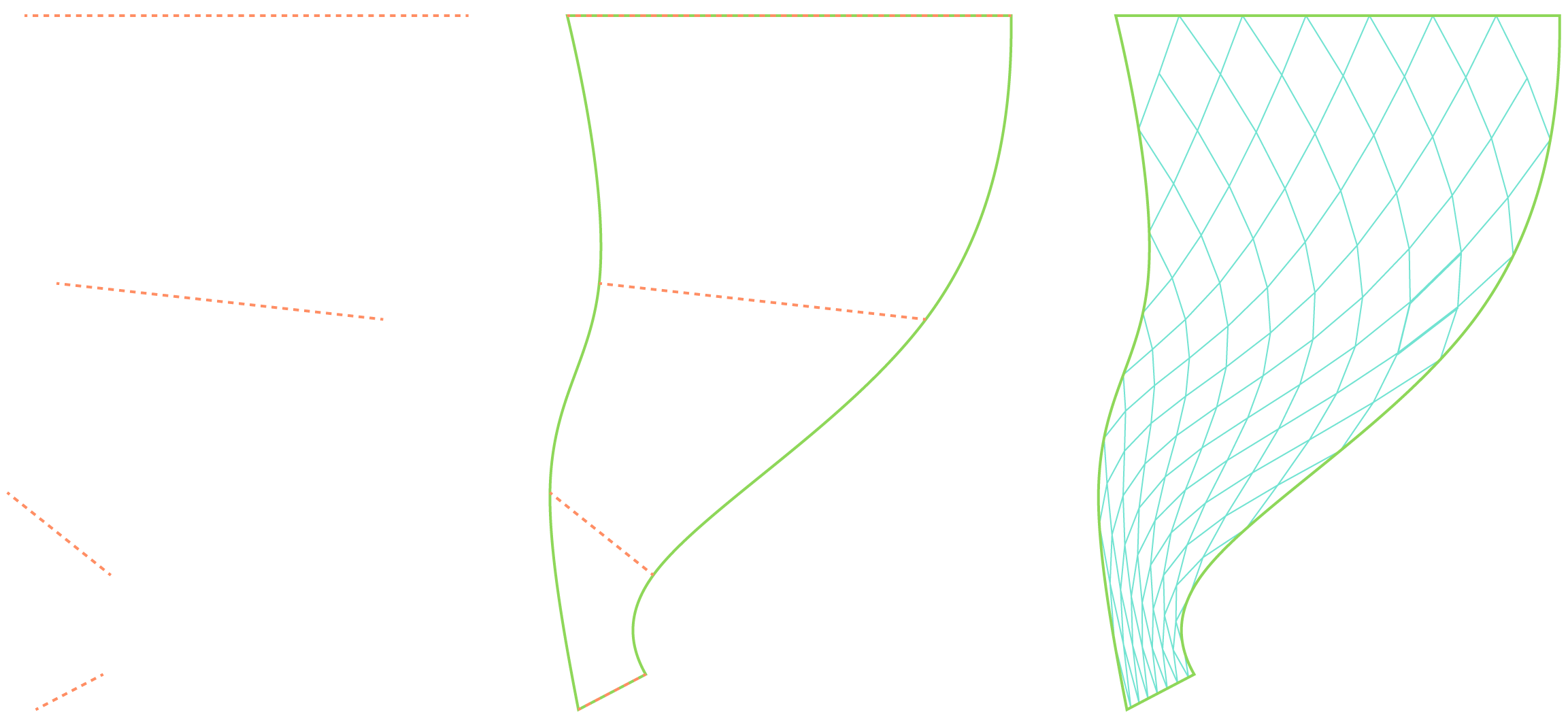

The reference model and definition for this project (downloaded from the link at the top of the page) attempts to reverse-engineer the broader pattern developed for this project.

To begin, a surface is constructed by lofting a series of curves. The script then divides the resultant surface into a grid of point and generates a diamond grid between them. The cells of this grid warp to conform to the surface and thus provide an initial layer of site-specific geometry.

A surface is lofted through a set of 4 base curves and a diamond grid is fitted across it.

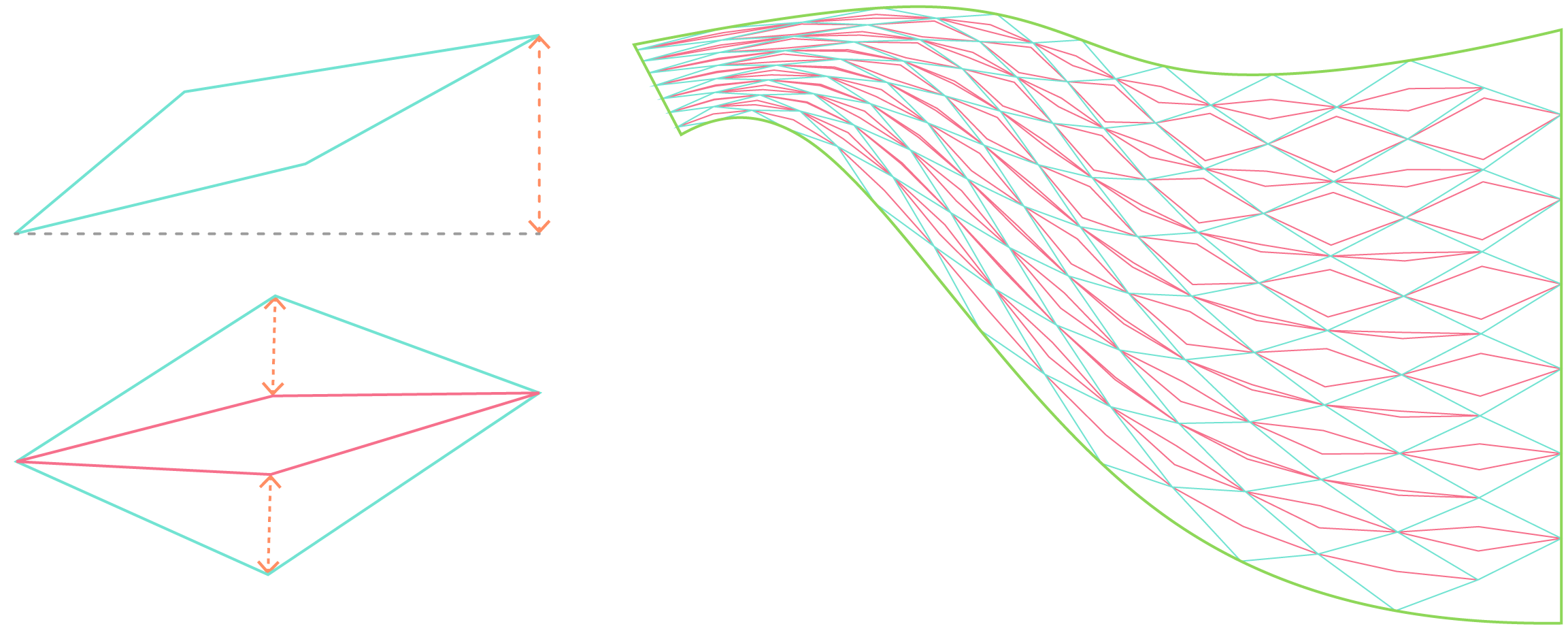

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comThe script then measures the vertical distance between the highest and lowest point of each cell. This difference is taken as a rough interpolation of slope and the value is ‘remapped’ to influence the width of each cell and thus control cell dilation. That is to say, the steeper the angle of each cell, the more that its inner wall becomes offset from its outer. Note: this mechanism is used speculatively and the actual Edaphic project likely had a different means of articulating the surface that seems to have incorporated the results of a gradient-descent method alongside other analytics.

The offset of each cell’s inner wall (left) is controlled by each cell’s vertical range (right). While the first layer of patterning conforms to the topography of a 3D surface, the second responds in size to a specific environmental input (in this case, slope).

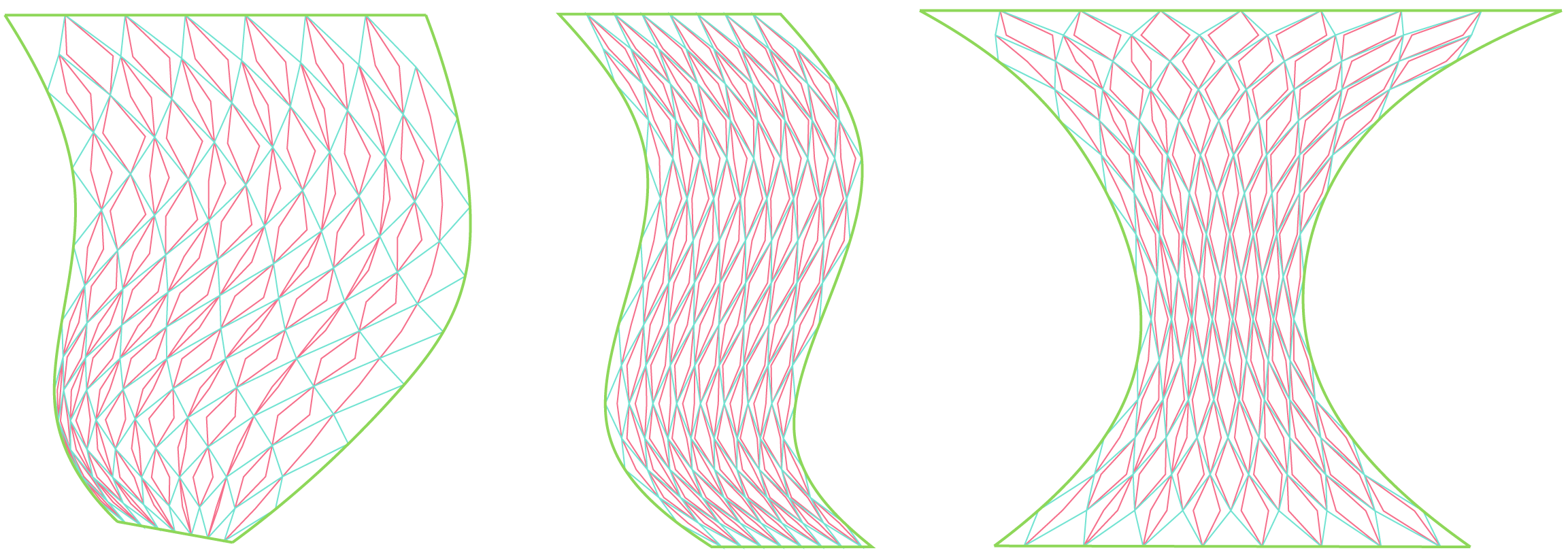

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comThe script has a versatility that allows it to be applied to a range of landscape conditions by re-configuring the underlying surface. This without even taking into consideration the additional variation possible when different data sets are introduced to influence the secondary offset pattern.

The pattern has a versatility that allows it be applied to a wide range of sites/ shapes.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.com-

M’CloskeyKaren and Keith VanDerSys, Dynamic Patterns (New York, NY: Routledge, 2017), 6.↩

-

M’Closkey and VanDerSys, Dynamic Patterns, 6.↩

-

M’Closkey and VanDerSys, Dynamic Patterns, 38.↩

-

Jillian Walliss and Heike Rahmann, Landscape Architecture and Digital Technologies (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2016), 170.↩

-

M’CloskeyKaren, “Dean’s Lecture Series 2016 - Karen M’Closkey,” 2016, https://youtu.be/v1Rsxr1pgjk.↩

-

M’Closkey, “Dean’s Lecture Series 2016 - Karen M’Closkey.”↩